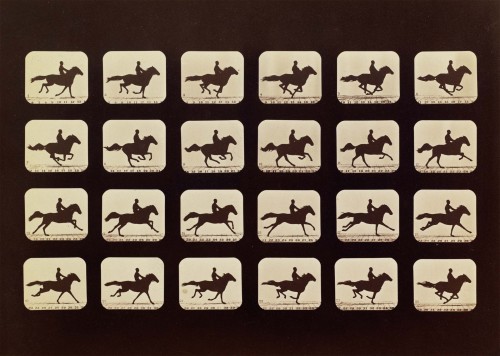

Eadweard Muybridge, Horses. Running. Phryne L. Plate 40, 1879, from The Attitudes of Animals in Motion, 1881. Albumen silver print. Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon 2006.131.7.

Helios: Eadweard Muybridge in a Time of Change at the Corcoran is the world’s first, comprehensive study of the photographer’s influential and inspirational career. Reigning over the field of photography for much of the second half of the 19th-century, Muybridge was a pioneer of the visual medium – bringing together both science and art in a seemingly effortless fashion. The exhibition includes over 300 elements, spanning from books – to albums – to stereographs (and even a Zoopraxiscope), all of which portray pieces of a process, establishing the foundation of the Muybridge legacy.

Born in Kingston, Muybridge immigrated to the United States at 21 years old. His career began in San Francisco as a publisher’s agent and bookseller, selling art and portfolio publications. While working in a field that was immersed in money, access, and power, Muybridge decided that he too wanted to make a name for himself; however, his dreams were put on a brief hold when he suffered a head injury – requiring the idealist to move back home and recover. But, by 1986, Muybridge, now a master of photography, re-emerged in San Francisco under the published pseudonym “Helios”.

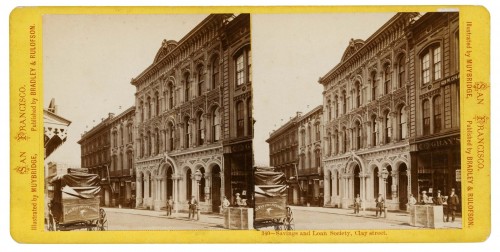

The exhibit takes you on a journey, starting with Muybridge’s stereographs. The stereographic card is an arrangement of photographs, printed side-by-side, so that when observed with a stereoscope viewer – a nifty little thing that forces the eyes to diverge – the perception is created that a third, 3D-type image has emerged. This composition was quite profitable for Muybridge, as there was a large market for these cards during his time; serving as an early form of entertainment before the existence of television or radio. My favorite stereograph on display is a self-portrait, in which Muybridge is depicted as a gold miner, indentifying himself with the San Francisco laborers that he preferred for his earlier subject matter.

Muybridge’s first professional shots focused on landscape, that of Yosemite Valley and the High Sienna, and architectural subjects, such as the construction of the San Francisco Mint – concentrating on vivid settings that challenged accepted notions of perspective. By captivating innovative shots, from the edge of a cliff to the underside of a mountain, he was able to create a sense of drama and depth that had never been depicted before. Furthermore, the waterfall became a constant theme for Muybridge because the site pushed perception even a step further – how could he represent water as a fluid subject, even though water appears as a solid in a single negative? This dilemma highlights just one of the many limitations of photography during this time, and also demonstrates how Muybridge sometimes had to manipulate his work in order to get the point across. I was fascinated to see how he created clouds, where clouds could not be seen, and added boulders, where boulders did not exist – such as in the photograph Mount Huffman, Sierra Nevada Mountains from Lake Tanay No. 48, 1872. Remember, this was way before the concept of ‘retouching’ or Photoshop existed.

Eadweard Muybridge, Savings and Loan Society, Clay street (340), 1869. Two albumen silver prints on studio card. Collection of Leonard A. Walle.

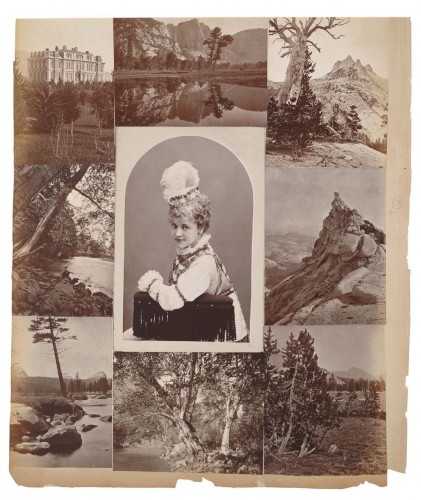

My favorite portion of the exhibit was where album pages from Muybridge’s photo studio are on display. The patchwork compositions each include both images of landscapes and theater portraits, and may have been created by his wife, Flora, as a means to express their, once happy, relationship (she was involved in the dramatic arts). Following the birth of their son, Muybridge found a photograph among his wife’s belongings that had the words “Little Harry” written on its back – which he believed implicated Major Harry Larkyns as Flora’s lover in an ongoing affair. Clearly, seeing no other solution, Muybridge killed Larkyns – leading to a spectacular murder trial with a truly Victorian outcome; he was acquitted, the death was justified.

A large part of the exhibit focuses on the latter, and probably more well-known, part of Muybridge’s career. After gaining much notoriety and fame for his work on landscapes, he was commissioned by Leland Stanford, former Governor of California and dedicated racehorse owner, to help him win a long-standing debate among racehorse enthusiasts: do all four of a horse’s hooves leave the ground at the same time during a gallop? With his new employment came endless funds and access to world famous engineers; providing Muybridge with the opportunity to develop new tools to assist in his research on the gate of a racehorse. It was during this time that Muybridge first developed the concept of stop-motion photography, creating a system of sequenced electric shutters that would allow him to break down a high-speed action into a still sequence.

Eadweard Muybridge, The Brandenburg Album of Bradley & Rulofson “Celebrities” and Muybridge Photographs, page 104, 1874. Albumen silver prints mounted to paper. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, Museum Purchase Fund, 1972.9.104.

Stop-motion photography became a huge success, making way for Muybridge to further expand his horizons. He began traveling, presenting a series of lectures called the Science of Animal Locomotion. During each lecture, he would show his sequences of animal movement in a projector, having discovered that as the machine moved through the glass slides, the segments of the sequence began to transform back into high-speed action. However, the projector didn’t move fast enough through the slides for Muybridge, so, in order to remedy the problem he developed the Zoopraxiscope – creating the projection motion picture and the origin of cinema.

Muybridge was brought on to continue his studies of animal movement at the University of Pennsylvania, photographing people and animals as they conducted different, often mundane –and arguably sexist as of today – tasks and duties. Animal Locomotion: An electro-photographic investigation of consecutive phases of animal movements, 1872-1885, a series of 781 stop-motion plates, across eleven volumes, has become Muybridge’s most famous piece of art – and fairly – the work that he is most often praised for, and emulated because of.

Regardless of how much – or how little – you know about this extraordinary character, I promise that this exhibit will not disappoint. It is definitely also worth going to see Muybridge’s contemporaries in the Exploration Gallery. The installation piece called A Dream of Pastures by Mitchell F. Chan and Brad Hindson allows the visitor to become a participant in their very own projection motion picture. And if that, and this clearly amazing preview/review, didn’t get you moving out the door – I am sure you are still wondering if Muybridge did finally set the record straight about the horse’s hooves….

Helios: Eadweard Muybridge in a Time of Change will be on display at the Corcoran until July 18th, 2010.

I didn’t have high expectations for this exhibit but was blown away when I finally saw it last weekend. What a massive collection!

His Yosemite photos appealed to me much more than those of Ansel Adams – so rich, haunting, and well composed. The stereographs didn’t do much for me especially since they were so small and mounted so low on the wall (the exhibit seems to be hung for short people!).

I loved the last room and being able to see the different angles that his stop action photos were taken from. The child who walks on all fours was freaky, and why was everyone nude?

One critique of the exhibit was the signage. Because the lights are turned down to preserve the work, it’s difficult to read the text that’s printed on dark paper. Strange call, Corcoran.

Pingback: We Love Arts: One Hour Photo » We Love DC