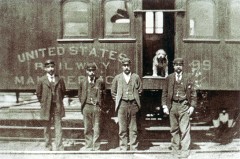

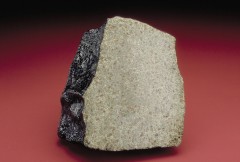

Pneumatic Mail Container; photo courtesy Smithsonian Institution and the National Postal Musem

Today’s Smithsonian Snapshot looks at another method of mail delivery that dominated the early 20th century metropolitan landscape: the pneumatic mail container.

In the late 1890s, networks of pneumatic tube systems were installed under city streets to move the mail. Each pneumatic tube canister could hold up to 500 letters. The canisters, also known as carriers, were air compressed through the system, traveling in a spinning motion at an average of 35 miles per hour. At its peak productivity, 6 million pieces of mail traveled through the system daily at a rate of five carriers per minute.

In 1893, the first pneumatic tubes were introduced in Philadelphia; in 1897, the service started in New York City. Boston, Chicago, and St. Louis also eventually incorporated the system. By 1915, six cities (including Brooklyn) had more than 56 miles of pneumatic tubes pulsing under the streets.

During World War I, the Post Office Department suspended the service to conserve funding for the war effort. After the war service was restored in New York and Boston. By the 1950s, it became clear that the end of pneumatic tubes was in sight as increasing mail volumes and changing urban landscapes made it impractical. While post offices and businesses moved with relative ease, the underground pneumatic system did not.